Since Thursday night, the English voters seem to have discovered a few things about the DUP - in particular, that they are opposed to abortion and same-sex marriage. These policies are enough to put them outside the political mainstream and to justify raising the question of whether they are suitable partners for Theresa May as she seeks to pull together a new parliamentary majority. But there is more to the DUP than its social conservatism. English readers might want to know a bit more about the small regional party that has suddenly found itself holding the balance of power in the Commons. These guys are quite unusual in a number of ways.

Where the DUP came from

From 1921 to 1972, Northern Ireland was ruled by a devolved administration in Belfast. The province's inbuilt Protestant majority guaranteed that the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) was permanently in power, winning election after election. The consequences of this permanent unionist hegemony were notoriously harsh for the Catholic nationalist minority. The results included their almost total exclusion from public life; endemic discrimination, particularly in jobs and housing; and a gerrymandered electoral system.

Opposition to this sectarian system came, of course, from the paramilitary IRA. Perhaps more seriously, opposition also came from the growing Catholic middle class; by the 1960s, this increasingly affluent and well educated section of the population was no longer prepared to tolerate being given second-class status. Tensions rose from the mid-60s onwards. By the end of the decade, peaceful civil rights protests had collapsed into inter-communal violence, and the British Army was sent in. The low point was reached with the notorious Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972.

Part of the story of these troubled years lies in the internal history of unionist politics. The UUP were mostly establishment conservatives rather than loyalist fanatics, and their Prime Minister, Terence O'Neill, had been pursuing what passed in 1960s Northern Ireland for a liberal, reforming agenda ("If you treat Roman Catholics with due consideration and kindness they will live like Protestants"). The short version of the story is that, as Northern Ireland fell into violence and disorder, the UUP began to split up; and the DUP was the main right-wing product of this splitting.

The DUP was founded in 1971, although it grew out of an earlier outfit known as the Protestant Unionist Party, which had been set up in 1966 and had older roots. While the nakedly sectarian "Protestant Unionist" label was replaced by "Democratic Unionist", the party's version of democracy was one which sought to hand all power in Northern Ireland to the country's permanent Protestant unionist majority. The founding father of the party was, of course, the Reverend Dr Ian Paisley, a charismatic fundamentalist minister and one of the few true demagogues in modern British and Irish politics. For years, the party was widely seen as standing in Dr P's considerable shadow.

The rise of Paisleyite loyalism forced the resignation of Terence O'Neill as Prime Minister in 1969. The former PM retired from politics altogether in 1970, and his seat at Stormont was taken by a jubilant Paisley. It was as if David Cameron's old constituency had switched straight to Nigel Farage.

The DUP in more recent years

During the long years of the Troubles, the dominant unionist party was still the UUP. On the nationalist side, the main party was the non-violent SDLP. The hardline parties - the DUP and Sinn Féin - failed to win over most voters in their respective communities.

The end of the Troubles reversed this situation. It was as if the voters of Northern Ireland now felt safe to separate out from the centre. This graph shows the respective share of the unionist vote that went to the UUP (blue) and the DUP (red) in general elections from 1974 to the present:

It is clear, then, that the DUP have widened their support since their days as a sectarian splinter group in the early 1970s. They have made some attempts to speak the language of diversity and inclusiveness. Ian Paisley himself struck up a famously close relationship with the former IRA leader Martin McGuinness during his time as First Minister of Northern Ireland - although it would be a mistake to think that this development was greeted warmly by other DUP members.

Perhaps surprisingly, the DUP have begun in recent years to entertain hopes that their social conservatism will win over right-wing Catholics, in an era in which both of the Catholic community's parties (Sinn Féin and the SDLP) are largely liberal and secular. These hopes have to date proved largely fruitless. The no-popery fundamentalist roots of the DUP are still showing. Earlier this year, the Irish Times journalist Andy Pollak wrote that the "anti-Irish and anti-Catholic bigotry of so many DUP-supporting unionists appears to still play a significant role in Northern life and politics"; although he did also acknowledge that "such bigotry is far less prevalent among younger DUP members".

In recent years, it is fair to say that the party has largely been run by what may be described as small-town conservatives - Arlene Foster, Simon Hamilton - rather than shariah-lite theocrats. We are talking UKIP-with-a-Ballymena-accent here rather than The Handmaid's Tale. Pollak estimated that 80% of DUP members would have been hardline fundamentalist Protestants in the 1980s, whereas only a third of DUP legislators at Stormont are still of that bent today. A third is clearly less than 80% - although it is still undoubtedly higher than the equivalent figure for, say, the Conservative contingent in the House of Commons. And there are other indications that the DUP is no ordinary political party. In 2008, its then leader Peter Robinson appointed a climate change denier, Sammy Wilson, as the Environment Minister at Stormont. This development would no doubt have been rejected by the scriptwriters of The Thick of It as being too implausible to make good satire. Wilson is one of the party's current MPs at Westminster.

It is interesting to note that the only MP that the DUP has ever had from outside Northern Ireland was Andrew Hunter, who represented the quintessentially middle-English constituency of Basingstoke on behalf of Paisleyite loyalism from 2004 to 2005. Hunter had previously been a member of the lunar right of the Conservative Party, and his Irish heritage led to him want to seek a more active role in the Irish political sphere.

Terrorism and political violence

It has been noted that it is ironic that a Conservative government which spent the election campaign digging up Jeremy Corbyn's ancient links with Sinn Féin should be so ready to get into bed with an outfit like the DUP.

When loyalist terrorists were interviewed and asked how they had got into paramilitarism, it is significant that Ian Paisley's name kept coming up as a source of inspiration. To be fair, Dr Paisley himself consistently denounced the loyalist terror gangs, with apparently genuine conviction. But that isn't the end of the story. Consider:

- As early as 1966, Paisley became chairman of a body known as the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee. This body disavowed terrorism, and its principal activity was to organise public protests; but it is accepted today that it also had links with paramilitarism.

- In 1981, Paisley assembled a group of about 500 people on an Antrim hillside. These people proceeded to brandish firearms licences showing that they had a legal right to own guns. This was interpreted by Paisley's opponents as a barely veiled threat of violence.

- In 1986, a loyalist group called Ulster Resistance (UR) was founded by a group of DUP members, including Paisley and our friend Sammy Wilson. People associated with UR were later implicated in arms dealing, although it is not suggested that this included any past or present DUP MPs.

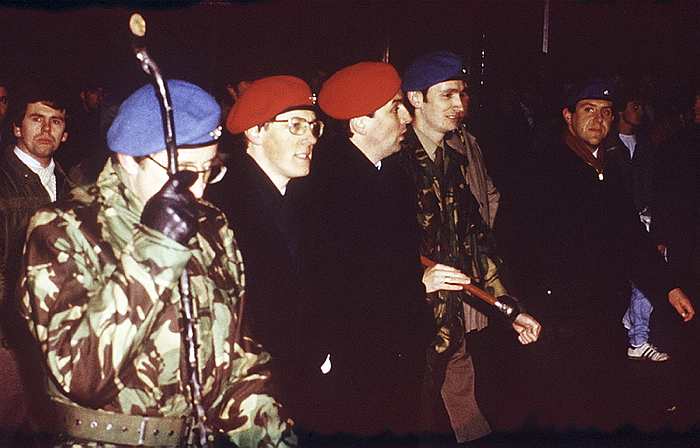

- Also in 1986, a group of loyalists, including the then DUP deputy leader Peter Robinson, made a brief but violent incursion into the Republic of Ireland, allegedly to highlight security failings in the Republic. This was the so-called "Clontibret invasion". It is believed that Paisley was originally meant to take part in it.

- In 2014, the DUP group in the Northern Ireland Assembly proposed a motion commemorating the disbandment of the notorious "B Specials" in 1970. The B Specials were not terrorists; arguably, they were worse, because they wore the uniform of the state. They were a brutal and sectarian police reserve force which even unionists don't usually bother to defend today.

- A body representing the surviving loyalist paramilitary groups endorsed three DUP candidates in the recent election. The party leader, Arlene Foster, rejected any support from paramilitaries.

Peter Robinson with Ulster Resistance members, 1987

What do the DUP want?

The DUP are not just a right-wing loyalist party. In fact, in some ways they are not really right-wing. In the field of economic policy, they have staked out a position as populist friends of the workers. In recent years, they have been seen campaigning for a higher minimum wage, reform of zero hours contracts and caps on energy prices. Conversely, they have taken up positions against the bedroom tax and the abolition of the triple lock on the state pension. These people are not Thatcherites with an ideological aversion to the government intervening in the economy.

In 2015, when everyone expected the general election to produce a hung Parliament, the DUP approached the polls with their hand held firmly out in the direction of HM Treasury. Their manifesto stated:

In broad terms, to secure strong and lasting growth in our economy we believe it best if government invests in the drivers for growth – enterprise, innovation, skills and infrastructure – to sustain and build the economic recovery. As a responsible party we want to see the budget deficit eliminated. However, we recognise that the rush to reduce and eliminate the deficit can have an impact on growth....

Among the fundamental budget requirements for Northern Ireland that we will campaign for are:

• A budget settlement which will allow real term increases in health and education spending over the next five years without decimating other key public services.

• Capital investment to make our schools and hospitals fit for the twenty-first century.

• Assistance to continue the reform and transformation of our public services.

Even for the DUP, ideology may count for less than pounds, shillings and pence, particularly in circumstances where there is the prospect of several billions of them flowing from London to Belfast. From this point of view, the DUP are not Tories. Indeed, it is their old foes, the UUP, who have been the Conservatives' allies in Northern Ireland. The DUP also seem to have had no problem getting close to Labour back in the days of Gordon Brown.

In this context, a few quotes from Hansard will suffice to illustrate some of the things that were on the DUP MPs' minds during the last Parliament:

In this context, a few quotes from Hansard will suffice to illustrate some of the things that were on the DUP MPs' minds during the last Parliament:

Does the Secretary of State agree that, to build and strengthen the economy of Northern Ireland, investment in infrastructure is absolutely vital?... Will the Secretary of State take the opportunity to reiterate to the Minister for Infrastructure that all EU projects that are signed off before we leave the EU will be funded even if they continue after we leave the EU? (Nigel Dodds, 26 October 2016)

May I personally thank the Secretary of State for the efforts she made in helping to secure a £67 million contract for the Wrights Group in Ballymena, which was very well received there, and for the work she did behind the scenes in securing that contract?... Will she, like me, ensure that, irrespective of the outcome [of the EU referendum], every effort is made to make sure that moneys released to the United Kingdom will be used to attract inward investment in Northern Ireland? (Ian Paisley Jr., 20 April 2016)

I thank the hon. Lady for giving me the opportunity to make it absolutely clear that 105,000 families in Northern Ireland will, as a result of this agreement, be protected in respect of tax credits. That is what the DUP has delivered. (Jeffrey Donaldson, 23 November 2015)They were even prepared to show concern for the poverty of single mothers, even if they did slightly spoil it by referring to them as "females":

The Minister will be aware of the continuing concern across the United Kingdom about the welfare reform proposals as they impinge particularly on women with young families. Will she keep under review that continuing concern... to ensure that there is no continuing disadvantage to females, particularly those with young families? (Gregory Campbell, 21 July 2016)At the present time, of course, the DUP's economic interests are inextricably bound up with Brexit. The party campaigned for Leave, but they are clearly worried about the consequences of crashing out of the European Union without a robust deal. The party's 2017 manifesto states, in a paragraph which is bolded for extra emphasis:

It is in the interests of all in Northern Ireland that the UK-EU negotiations progress well and that the trade elements commence as soon as possible. The stronger and more positive the agreements reached, especially on trade and customs relationships, then the better for the particular circumstances of Northern Ireland.

The party's line is that it wants to see a "frictionless" border with the Republic of Ireland, but no new border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. These two policies, taken together, would rule out the UK leaving the single market and customs union as Theresa May has promised. The implications of this are substantial, and have only just begun to be digested.

Northern Ireland is a place of surprises. It would be one of the bigger surprises of my own lifetime if it was the forces of Paisleyite fundamentalism that ended up protecting the UK from the disaster of a hard Brexit. NO SURRENDER!